Magic Mountain

Chapter 3 - Open Season

Estimated Read Time: 18 min

This is Chapter 3 in a multi-part series on Magic Mountain. If you prefer to start from the beginning, please check out Chapter 1 and Chapter 2.

Nearly 6 weeks after Magic Mountain opened its gates for business, the new family-fun center’s most iconic attraction was finally ready to open. The Sky Tower was Magic Mountain’s ultimate landmark. The white lattice tower could be seen reaching for the sky from miles around, boldly declaring the presence of the new theme park. But despite vertical construction finishing in January, only one elevator was functioning by the park’s opening day—and the state required that both elevators should work to operate.

Finally, in the first week of July, the attraction was ready to go. A Signal reporter was invited to Magic Mountain to examine the new experience. The reporter was whisked to the pinnacle of the park, where the tower stood. There, a small crowd gathered waiting for the next elevator. The reporter explained how when the “walkie-talkie girls in their short-skirted uniforms, gave a sign...the doors to the tower’s elevator slid open.” The crowd piled into the glass and steel, irregular pentagon-shaped elevator car. Before claustrophobia could set it, the elevator began sliding up the tower, revealing the surrounding landscape through the cab’s large windows.

At the top, the reporter got out to examine the observation decks. The lower deck featured open-air views while the upper deck was fully enclosed with large window panels. Other than the walls and windows, the two levels were relatively sparse, save for a few metal telescopes. And the tower “[swayed] noticeably in even a gentle breeze.”

A park spokesman assured the reporter of the tower’s structural integrity, before continuing: “We’ve got some plans for the observation decks. We’re planning to blow up some pictures of some of the things to be seen from the tower and put them on the wall.”

And what could be seen?—haze. It was 1971 and Southern California was still in the worst of its smog problem. Air pollution had drifted from Los Angeles into Valencia and nested between the mountains, blocking the view of anything interesting.

The reporter wrote: “We looked to the east—Valencia Valley was covered by a thick haze. To the west the dry brushy mountains faded into the dusty sky... ‘The tower should be great around Christmas time,’ said one visitor as he twisted the telescope’s focus dial in vain. ‘But right now that Los Angeles smog defeats the whole purpose of the thing.’”

“There’s a lot you can see from up there,” the park official assured the reporter. “But of course you need a clear day.”

The reporter was unimpressed. Still, the reporter conceded that the Sky Tower offered one brilliant view, if you looked in the right direction: “The best view was straight down. You could see every ride in the park, and for a dime you could look through a telescope and pick out the faces of your friends below.” This anecdote is in the spirit of how Magic Mountain’s first season transpired. Many rides opened late and things didn’t work as intended. And yet still, the infant theme park was a sight to behold.

The Benefit of the Doubt

In March of 1971, before an opening date had even been set, it was already decided who would have the distinction of visiting Magic Mountain first. The theme park decided to host their press-preview in tandem with a celebrity benefit for the Reiss-Davis Child Study Center, an institute (in the parlance of the time) “engaged in research and treatment of emotionally-disturbed children.” The event was to be hosted by singer-songwriter-composer Burt Bacharach and his then-wife, actress Angie Dickinson. The two co-chaired the benefit for their daughter, Nikki. The event would turn out other big names, including Paul Newman and Joanne Woodward, Lucille Ball and her then-husband Gary Morton, Gene Kelly and Jeanne Coyne, Frank Sinatra, and some-fifty other known actors, filmmakers, comedians, artists, and musicians. As the construction timeline finalized, the event was penned for May 22. This would give the theme park one week of trial operations or previews before a grand opening on May 29.

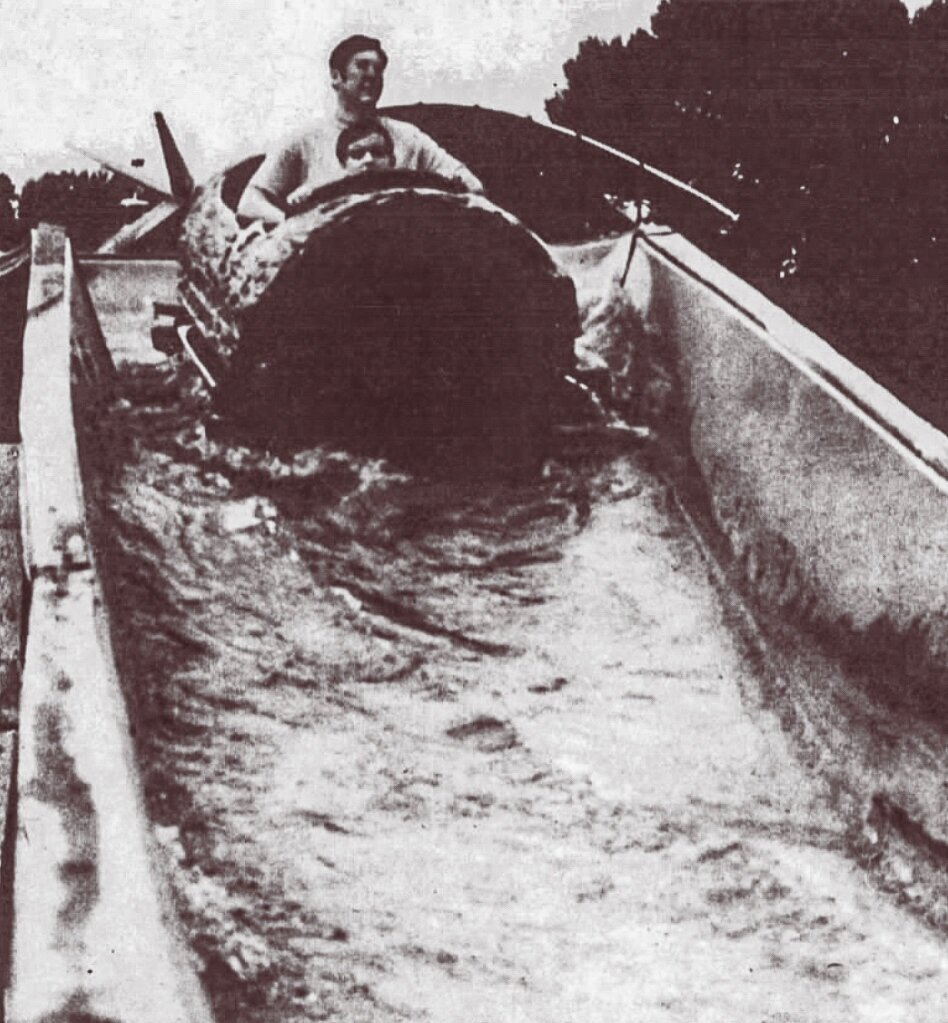

During the benefit, Log Jammer suffered a mechanical failure that kept the ride closed through opening day.

When the day of the benefit arrived, the mood was notably chaotic. Members of the press and television-Guests arrived at 8:00 am and found no one from the park there to greet them. The gaggle was finally let into the park at 9:30 and yet, rides were not yet running. Once the park finally awakened, the rides that were operating struggled to keep up with the 14,000 benefit Guests in attendance. Five major rides were still not open and two-hour lines formed for those that were. Included in a rather scathing review of the new park by L.A. Times writer Mary B. Murphy, park-goers could allegedly be overheard saying “the lines move so slow I’m bored” and “after all that waiting I”m not sure it was worth it.”

There were other problems too. Murphy cited bathroom doors that didn’t close properly, or a shortage of toilet paper in the ladies room. One unlucky guest had to deal with a blue paint stain on their rear after leaning on a freshly-painted handrail. And when it came time to leave, guests found that the parking lot lacked directional signage and couldn’t find their way out of the vast sea of cars. For Murphy: “One could safely call the opening a rush job. Magic Mountain met its deadline and is now going about the job of filling in the pieces it left out.” And yet, the park couldn’t fill in all the pieces by opening day.

For All Who Come to this Magic Mountain

On May 29, 1971, a cool, gloomy spring day, Magic Mountain opened its gates to the general public. Even with the additional week of preparations and a community preview night, the park still appeared in many ways unfinished. Just over 10,000 guests descended on the new park, leading to traffic in the still under-construction Newhall Pass. Tram drivers did their best to give descriptive reminders of where their passengers had parked in the still unnumbered parking lot. Then, they politely spieled for mercy, announcing: “We’re happy you’re here to enjoy Grand Opening Week. And we hope you’ll understand that, in a park this size, last-minute adjustments of the facilities are always necessary. As a result, a few of our rides are not yet operating.”

The cover of a massive, multi-page advertising supplement in the Los Angeles Times, published on June 13, 1971.

As established, the Sky Tower was still not operating. The Funicular still ferried guests up the hill to the closed attraction (although on one reporter’s visit, upon approaching the transport ride it shut down and “three blue-shirted mechanics scrambled up the hill” to troubleshoot). On the other side of the park, the double-Ferris wheel Galaxy, the largest flat-ride in the park, was still mid-construction and had caged-gondolas peppered around the ride’s base, awaiting installation. “We’re waiting for a part from Chicago”, a park spokesman fumbled. The Log Jammer, which operated a week early during the charity benefit, suffered a major mechanical failure and was inoperable on the opening day (a few weeks later, it also suffered several rear-end collisions, sending Guests to the hospital and causing further downtime). With so many rides closed, the park offered opening day guests coupons for half-priced admission on a second visit, to be used before Labor Day.

Guests examined the park and shared their opinions on what the park had going for it, and what the park lacked. Some wanted more rides. More benches. More themed areas. Many enjoyed the landscaping, or rides on The Gold Rusher, El Bumpo, and the Grand Prix automobile course. And most agreed that, as the park matured and rides opened, it would be a great place to visit. Even Mary B. Murphy left lines in her negative review to concede to the potential in the park. Writing on the park’s atmosphere and admission price, she compared the venue to Disneyland, stating “Magic Mountain is more pleasant in its pastoral setting and more intimate. It is to Disneyland as San Francisco is to Los Angeles....Magic Mountain is also less expensive.” She continued, “Given a few months to work out the kinks, Magic Mountain may live up to its name. In the meantime, bring along a lot of patience.”

Something To Keep Coming Back For

For all of the biting press about ride reliability and fumbling park operations, there was a feature of the new park which appeared well-received—the entertainment.

Bugs Bunny with a guest during the May 22 benefit.

A purposeful element of Doc Lemmon’s operating strategy and a nod to Sea World’s animal-show roots, Magic Mountain invested a great deal of money and energy into in-park entertainment, starting with the characters. While those with some knowledge of Magic Mountain in the ‘70s might be familiar with the park’s home-grown characters, for the opening season, Magic Mountain ironically featured the Looney Toons. Looney Toons characters were positioned as a worthy counter-point to Disneyland’s characters and were a highlight for young visitors. Mary B. Murphy acknowledged the benefit of the characters, explaining “the staff at Magic Mountain tried to make queueing pleasant. Cartoon characters like Bugs Bunny, the Road Runner and Daffy Duck were sent to overcrowded areas to keep the kids happy and take pressure of their parents.”

For other entertainment, the park contracted Larry Sands Productions to stock the park with a revolving variety of entertainment acts. According to one advertisement, “the whole park bubbles with clowns, jugglers, tightrope walkers and other circus acts at strategic locations. Troups of mobile magicians and other entertainers are constantly on the move around the park, while strolling troubadours fill the streets with song and even serenade diners at the Four Winds and other restaurants.” The park advertised a planned entertainment budget exceeding $1 million annually to deliver new and alluring acts.

A promotional photo of the 7·Up/Dixi Cola Showcase Theatre. The venue was later named the “Golden Bear Theater” and is still used for special events.

The crown jewel of Magic Mountain’s entertainment was a rotating lineup of celebrity acts to be housed in the 7·Up/Dixi Cola Showcase Theatre. This 3,400 seat covered amphitheater was nestled into the park’s eastern hillside and was designed to support musical acts and plays. The park advertised that the theatre contained an “automatic lighting system…among the most modern in the world”, “top quality” sound system, and a stage area that “compares favorably with the Ahmanson Theatre” in Los Angeles. But the real showcase in the Showcase Theatre was expected to be an assortment of celebrity acts. The theatre’s inaugural acts featured the Jimmy Durante show and Lohman & Barkley. As the summer progressed, well known musicians and comedians were booked to play the Showcase Theatre, including Mel Torne, Milton Berle, Phyllis Diller, Frank Gorshin, Pat Boone, and Sonny and Cher. As with the rides, these celebrity acts were accessible for no additional charge and were included in the cost of admission.

The park also placed a great deal of stock in its three dance pavilions as a means of attracting “couples and youngsters from eight to 80.” The largest dance floor was located in the north-west corner of the park, near the arcade area (in front of where the DC Universe area of the park is now). This dance area featured an elevated stage, sunken dance floor, and was expected host 300 dancing couples with up-tempo dance music and rock. At the front of the park a second dance area, two-thirds the size of the first one, would cater to couples and slow-dancing. And finally, the third dance area was attached to the Four Winds steak house, allowing for a nice meal, slow dance, and music “by sophisticated trios.”

For Doc Lemmon, this assortment of character, small-act, celebrity, and dance entertainment—all included in the cost of a ticket—was a foundational part of Magic Mountain’s business strategy. Lemmon admitted, “If we want people to keep coming back, there has to be something to keep coming back for. Guest celebrities in the Showcase Theatre and bands in the three dance pavilions are changed every week…Unless you check the entertainment section of the local newspaper at least once a week, you are likely to miss something here you would really like to see.”

Even with the constant churn of entertainment acts, the initial press about closed rides might have dampened early season attendance. By August, the park started to increase efforts to drive in visitors. Coupons for half-price tickets began to show up at local grocery stores. And the park started hosting events and giveaways, like “Fiesta Week”, which celebrated Mexican-American Friendship and featured a nearly 8 foot tall piñata. By the end of the month, industry watchers were growing unsure if Magic Mountain would end up in the black for its first season. And yet, no one anticipated the actual shake-up that was coming.

The Sea Dries Up

Suddenly, on September 21, 1971, three years after Sea World first began work on their “rides park” concept, the organization announced that they were withdrawing from their participation in Magic Mountain.

An advertisement for Sea World in the original Magic Mountain Advertising Supplement.

As a part of this move, Sea World Inc. agreed to sell its 50% stake in Magic Mountain to the Newhall Land & Farm Company. Over the next two months, the two companies hammered out the terms of their divorce: Sea World would pay $400,000 to cover losses and fixed expenses through the end of 1971 while the Newhall Land and Farm Company would issue a $2.5 million promissory note for Sea World’s ownership stake. Sea World was expected to take a nearly $3.9 million loss on the project (although the firm cited tax credits would bring the figure to just under $2 million).

Reporting on the rift initially suggested that Sea World lost interest in the project after an expensive first season. A Sea World spokesman admitted that the park had cost over-runs of more than 20% and that the entire project was $7 million over budget. Additionally, though the park had recently welcomed its one millionth guest, summer attendance came in below expectations. Ride reliability was challenged and guest complaints were high, particularly in the first half of the season when several major rides were still closed. It was clear the park would require significant additional investment to address many of these first-season concerns.

While there was truth to these elements, the primary factor in Sea World’s withdrawal was the company’s refocusing of energy on the east coast. At the time of the September 1971 announcement, Walt Disney World was 10 days away from opening and Orlando was fast-becoming host to the next big regional park boom. Sea World Inc. had already announced plans to open a third Sea World park in Orlando and their financial commitments at Magic Mountain burdened this strategy. In one press release, Sea World shared that there were “substantial unanticipated additional capital requirements for Magic Mountain, and restrictions contained in agreements with lenders”. A Sea World spokesman confirmed these burdens “would have indefinitely delayed or possibly precluded the further development of Sea World of Florida.” For the expansion-hungry organization, it made more sense to walk away from their experimental rides park’s commitments and double-down on their established marine park brand in an up-and-coming region.

Doc Lemmon (left) with his original Magic Mountain management team.

Following the announcement of Newhall Land’s full ownership, several members Magic Mountain’s core, Sea World-hired leadership were purged—a mini executive “Red Wedding” of sorts. Security chief Robert Rollins was removed; his departure was quickly followed by Mike Broggie, director of public relations. And Eugene “Doc” Lemmon, Magic Mountain’s General Manager, chief promoter, and “idea-man” who had ferried the park from idea to reality—was out.

James Dickason, president of the Newhall Land and Farm Company, immediately made his rounds with the press to instill confidence in the land management company’s ability to operate a theme park. To own and operate Magic Mountain, Newhall Land formed a wholly-owned subsidiary, called Valencia Recreation Enterprises Inc. To lead the park, Newhall Land promoted Terry Van Gorder, the manager of their golf courses and the Indian Dunes motor recreation park. Dickason assured the press that guest complaints no longer plagued the new park. And yet, he boldly declared that Newhall Land was “going to do nothing but improve” Magic Mountain, further stating “we’re going to keep adding [rides] ‘till doomsday…there are going to be big additions next year and even bigger ones the year after that.” By November, Newhall Land was announcing plans to invest an additional $4.5 million to expand and improve Magic Mountain, confirming that “‘a major water thrill ride’ and additions in the children’s area are being planned”.

For all of the challenging press, horror stories, and early incidents, Magic Mountain broke even in its first season. The park succeeded in offering something for everyone and put Valencia on the map for the Newhall Land and Farm Company. It introduced the concept of an all-inclusive, single-price theme park admission to the Southern California area, a model Disneyland would adopt in 1982. And it introduced Southern California to its first mine train coaster. While the Newhall Land & Farm Company was inexperienced in the space of theme park management, the land company had the incentive and the resources to ensure Magic Mountain would succeed. The company would invest heavily in their theme park over the course of the ‘70s, transforming Magic Mountain from an experimental rides park into a nationally known entertainment destination. But, it’s time for me to go back to watching my kid—that story will have to wait for a later date!

Lemmon's Denouem(ountain)

The Signal finally caught up with the unemployed Doc Lemmon at his house, just west of Castaic Junction, on October 28, 1971. The house, ironically a lease from Newhall Land, was hardly the site of self-pity or rage. In fact, Doc hardly let any time pass to process his dismissal before jumping straight into his next endeavor. Reaching back to his Stanford Research Industries days, Doc established consultation business to research the “feasibility, profit potential, and design of amusement parks”. He alleged that he already engaged with four multi-million dollar clients who were requesting his design assistance—but that details were highly confidential.

When pressed on his time with Magic Mountain, Doc refuted the notion that the park wasn’t doing well. To him, early criticisms are just part of the process for honing a new theme park experience. “It’s done as well as any new park. Disneyland had a lot more trouble,” Doc suggested. Though so much was still uncertain for Magic Mountain’s immediate future, Doc remained confident: “That little place over there is going to flourish. You’ve got to give it about three years.”

And while perhaps The Signal reporter half-expected a rant about his dismissal, Doc expressed no bitterness about getting canned. For him, the past three years cemented a legacy that would place him in the rarefied company of other theme park founders. After spending years consulting, planning, commanding, scrambling, and arguing over other companies’ theme park operations, he had created a destination for himself. Walt had his Land, and Doc had his Mountain. And for that, he was at peace, closing, “I’m kind of like the author; I wrote the book. I wish it all the success in the world.”

Not long after I started this “Amusement Archives” project, I had the realization that Six Flags Magic Mountain—my home park and a place I have great history with—was due to celebrate its 50th anniversary this year. And while Disneyland turned its 50th into an 18-month celebration and Knott’s Berry Farm is currently doing the same for its 100th, it felt like Six Flags wasn’t really acknowledging this milestone. The chain, not known for nostalgia-based marketing, has focused its messaging on reopening from COVID-19-related closures, in-park safety features, and hiring (theme parks are struggling from the same inability to woo workers as other service-based industries).

All of this to say, I didn’t want this milestone to go unacknowledged. I set out to craft a “comprehensive history of Magic Mountain”—much in the approach that Chris at Airtime Thrills is doing with his amazingly thorough, 5-part documentary series on the park’s history. But in addition to work and and parenthood slowing my ambition, I kept digging into fascinating stories about the park’s pre-opening years. And thus, these first three chapters were written to celebrate the park’s 50th.

I’m going to pause on writing about Magic Mountain for a bit and focus on other stories, but I hope to revisit the next few eras of the park in the coming months and years. I expect that I will be able to continue this story, albeit picking up the pace some. But if you’re interested in the next few chapters of the park’s history, I recommend checking out the aforementioned Airtime Thrills, decade-by-decade documentary of the park or visit SCV History for some great photos and writing on the park. Anyway, thanks for reading and I’ll see you in the next post!

Photo Credits

Cover Image - The Gold Rusher - From an advertising supplement to The Los Angeles Times, June 13, 1971.

At Last — The View From The Top Of The Mountain - From “At Last — The View From The Top Of The Mountain”, The Signal, 7/7/1971.

Log Jammer - From an advertising supplement to The Los Angeles Times, June 13, 1971.

The West’s New Family Funland - From an advertising supplement to The Los Angeles Times, June 13, 1971.

Happy Armful (Bugs Bunny) - Photo by Kathleen Ballard. From “Opening-Day Jitters at Magic Mountain”, The Los Angeles Times, 5/25/1971.

The 7·Up/Dixi Cola Showcase Theatre - From an advertising supplement to The Los Angeles Times, June 13, 1971.

Sea World Advertisement - From an advertising supplement to The Los Angeles Times, June 13, 1971.

Magic Mountain Management - From an advertising supplement to The Los Angeles Times, June 13, 1971.