The Dragon’s Gorge

Part 1 - Landing at Coney Island

Estimated Read Time: 8 min

“Come, Love, get in and let us try

The slippery Dragon’s Gorge.

You say you think you’re going to die?

Oh well, hang on to George!

Why do your features lose their youth?

Why wear that sickly frown?

(I think, dear Love, that was a tooth

You dropped while coming down.)”

—Wallace Irwin,

in the poem “Why They Go”

August 13, 1910, The Saturday Evening Post

On April 23, 1905, Coney Island’s Luna Park soft-opened to the public in advance of the venue’s May 13th opening date. 5,000 visitors poured into the New York amusement park eager to see how the place had changed from the previous season. They explored the freshly remodeled space and partook in several of the classic rides, like “Shoot the Chutes” or “A Tip to the Moon”. But where the “20,000 Leagues Under the Sea” attraction stood the year before, a new structure had emerged.

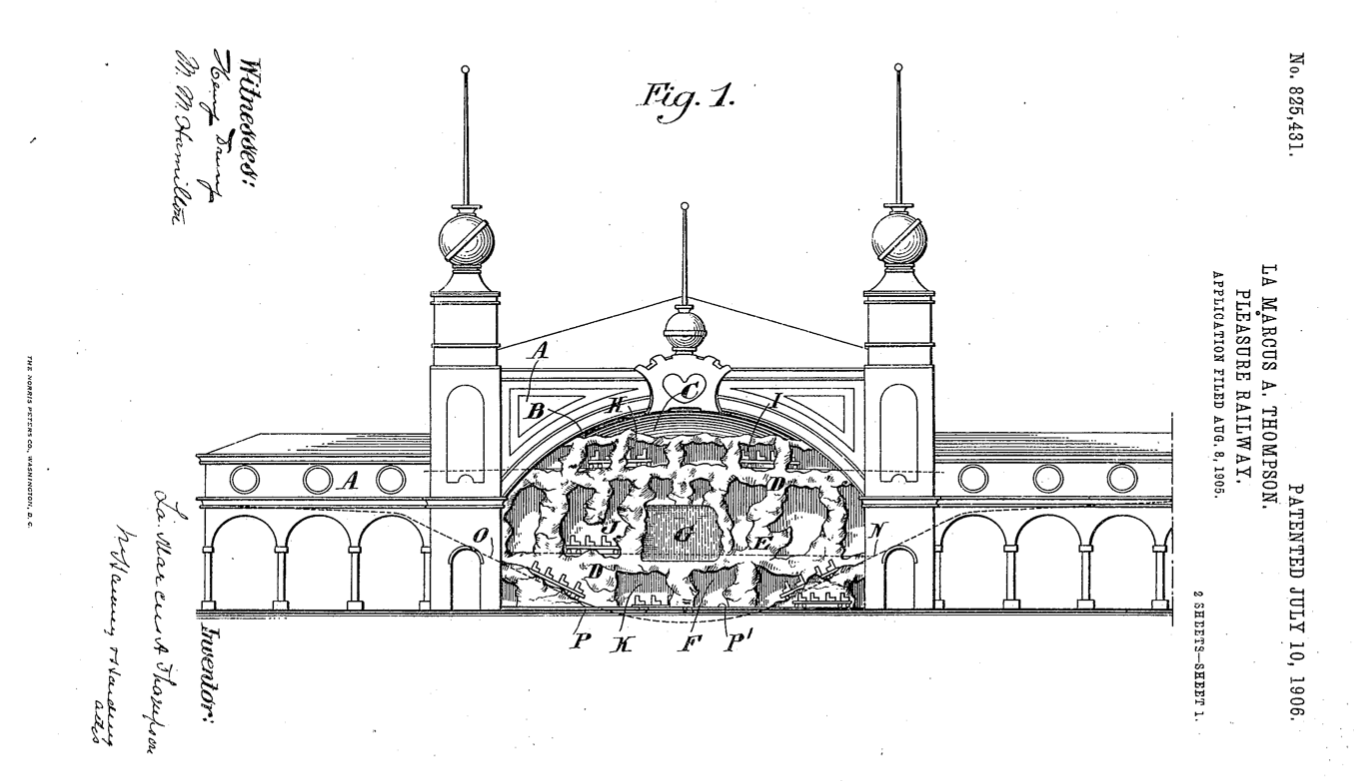

The large, 300’ by 200’ building was flanked by two towers, each decorated with an imitation pagoda and metal globes. Like a shoebox diorama, the middle of the building featured a massive arch cutout, giving curious spectators an inside view of roller coaster tracks winding through a rocky grotto. In the center of rock work, a 30-foot waterfall gushed down a small ridge behind the coaster tracks. The outside of the structure had fancy ornamentation, an assortment of flags, and Luna Park’s signature “heart” icon. And on each side of the central arch was the building’s key feature—two great dragons, complete with green, glowing eyes, standing guard. The dragons, built of steel, wood, wire, burlap, and plaster, were reported to stand 45 feet tall and each featured a 75 foot wingspan. Though early advertisements and news clippings referred to the ride as “Coasting the Gorges”, the ride’s name was quickly changed to “The Dragon’s Gorge”. With such menacing guardians, it’s easy to understand why.

The Dragon’s Gorge was being constructed for Luna Park by La Marcus A. Thompson and his Thompson Scenic Railway Company. Thompson is a behemoth figure in the history of roller coasters and I’m sure to write more on his story in the future. He developed and built the “Switchback Railway”, considered by many to be the first purpose-built roller coaster. The contraption opened at Coney Island in 1884 and was an instant success. But as others began to copy and enhance the design, kneading the structure into the ride we would better recognize as a modern wooden roller coaster, Thompson went in a different direction—leaning into scenery, or theming. In a 1910 bio in the Saturday Evening Post, writer Isaac F. Marcosson explains:

“Gradually the rides became longer and the inclines steeper, but soon Mr. Thompson perceived that to hold and increase business he would have to give the public a novelty…So Mr. Thompson said, ‘They are tired of looking at the ugly trestle; I will give them something pretty to look at.’…he built what he called a scenic house, made of wood and papier-mâché, which had cycloramic walls. As they rode along, the passengers on the cars got the impression that they were going through a grotto. Hence came the name of Scenic Railway”.

Thompson’s themed Scenic Railways merged his roller coaster concept with theatre, architecture, and art. The rides flung passengers through dark tunnels, past 360-degree dioramas (known as cycloramas—like Disney’s Circlevision but with a static, painted image), and eventually through artificial rock work and mountain ranges. In The Incredible Scream Machine - A History of the Roller Coaster, author Robert Cartmell reveals, “Thompson, surrounded his tracks with elaborate artificial scenery. Not content with cheap cardboard landscapes, the Scenic Railway used beautiful grottos in blue and purple with blinking colored lights. At strategic points cars tripped switches and flood lamps illuminated tableaus or Biblical scenes.”

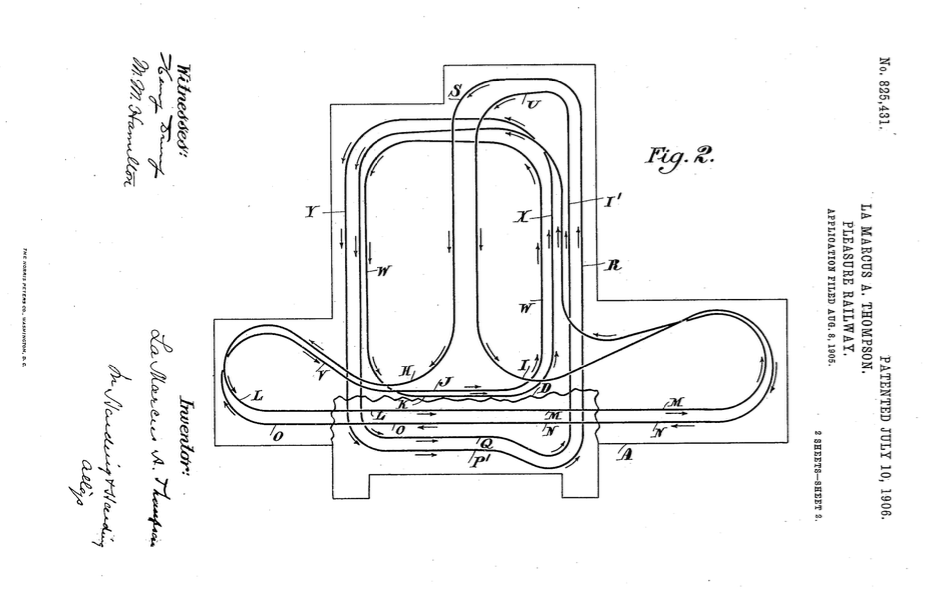

With the ‘The Dragon’s Gorge’ attraction, Thompson sought to elevate the scenic railway concept from one entering a “scenic house”—or show building, by modern nomenclature—to fully encompassing the attraction within the building. This allowed Thompson to fully hide the ride’s structure and control the scenery in the experience. But Thompson was aware that fully enclosing the railway would make the ride experience unknown to passers-by on the midway. In a patent application filed in August of 1905, Thompson goes to great lengths to explain that the focus of the invention was the open-archway, featuring the railway threading through a sample of scenery. Thompson explained: “By this arrangement a novel pleasure-railway is formed which not only gives pleasure to the rider but also to the spectator, who stands in front of the arch or opening, the rider being brought suddenly from a point of obscurity to a point of full view of the spectator, only again to be suddenly withdrawn from view.” Though sans dragons, diagram in the patent is undeniably “The Dragon’s Gorge”, complete with the arch, towers, similar decorations, and the heart-icon of Luna Park prominently anchored to the facade.

The Dragon’s Gorge finally opened at Luna Park on May 20, 1905. For 10-cents, patrons could zip around 4,800 feet of track through inclines, drops, curves, and a variety of show-scenes. Instead of telling a single, specific story, the show scenes depicted recent news-worthy moments—some of the big stories of the day.

These dioramic scenes included:

The North Pole or Arctic, complete with Inuit people hunting polar bears from canoes (in the decade prior to 1905, several failed attempts were made to reach the North Pole; the pole would finally be reached in 1908/09)

Havana Harbor the morning after the destruction of the U.S.S. Maine (a Navy ship sunk by explosion on February 15, 1898, kicking off the Spanish-American War)

The Battle of Port Arthur, a famous naval battle between Russian and Japanese vessels (which took place February 8 and 9 in 1904, during the Russo-Japanese War)

Rocky Mountains, with a Native American encampment on top

The Rocky Mountains scene concluded with a 60-degree drop to the bottom of the gorge, serving as the ride’s grand finale.

The ride ran multiple vehicles at once, keeping each evenly spaced with on-board brakemen who used a series of block-signals to safely proceed into the next zone. Still, accidents happened. Three months after the ride’s opening, a vehicle derailed and was struck by another vehicle following closely behind. Passengers experienced contusions, abrasions, cuts, and “hysteria”, but no one was badly injured and the ride quickly reopened. Other visitors feared that the scenery was too close to the ride and that “if a person became careless or unconsciously poked his head out the side of the car, he would be badly injured.” Despite such warnings, the new ride was a roaring success.

Visitors were thrilled by the attraction’s speed, darkness, and scenery. Luna Park, managed by Frederic Thompson, was famous for reinventing itself season after season, tearing down rides and attractions that no longer drew the public’s interest—but The Dragon’s Gorge was popular enough to live on with few alterations. Five years after opening, the attraction was still reported as doing “large business”. Frederic Thompson attributed the success of the ride to an American predilection for speed, stating: “We as a nation are always moving, we are always in a hurry, we are never without momentum. ‘The Dragon’s Gorge’ [and] the thousand and one varieties of roller-coasters are popular for the same reason that we like best the fastest trains, the speediest horses, the highest powered motor-cars, and the swiftest sprinters”.

On July 6, 1912, a fire was discovered in an employee dressing room within the building. Smoke began to pour out and “choke up the tunnels” of the railway and an alarm was sounded. This sent the park’s fire department, made up of retired city firemen, into action. At the time, Luna Park had a robust fire plan and firefighters were assisted by 1,500 male park employees, each with a designated role in case of fire. The Sun newspaper shared, “the number includes even the dwarfs and ballyhoo men” and joked that “not many fire departments in action can show the variety of costumes, from tights to military togs, which the park’s employee showed when they jumped to their stations.” With 20,000-40,000 people in the park, reserves from the Coney Island police arrived and controlled the peeping crowd as they watched the firemen work.

Luckily, the fire was extinguished within 30 minutes and The Dragon’s Gorge building was largely spared, with little damage. The park’s attractions continued operating and park officials, led by Frederic Thompson, struck up the band and formed a procession to distract Guests, keeping the crowd in good spirits. Their showmanship worked and, save for a few newspaper clippings, the fiery outburst would fade away into Luna Park history.

But it wasn’t the last time the dragons would breath fire.

Thank you for reading the first entry in The Amusement Archives! I am actively working on Part 2, which moves our story to Venice Beach, California. I hope to be able to post, soon!